|

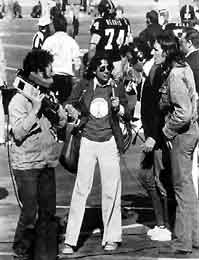

(From left to right) Bart Friedman, Nancy Cain, Tom Weinberg, and Elon Soltes critique CBS' coverage of Super Bowl X (1976) in TVTV SUPERBOWL, a video documentary that takes an irreverent, behind-the-scenes look of America's love of pro football. |

The

Challenge of Creating an Afterlife for Media The setting of Hirokazu

Kore-eda's film "After Life" (Japan, 1998) is purgatory, but it's

not a limbo where departed, suffering souls expiate their sins. In

this version, the dead aren't required to atone for misdeeds, but

to reflect on their past. In Kore-eda's vision, purgatory is a shabby

state archive where sincere workers execute bureaucratic functions

with efficiency and courtesy. Staff archivists perform an intake of

the clients, calmly inform them that they are dead, and instruct that

they must choose a single memory from their entire lives as a keepsake

for all eternity. The characters recall and relish sights, smells,

sensations and tastes. Memories include an awkward conversation between

lovers on a park bench, a solo flight in an airplane, a dance in a

red dress, and a shower of cherry blossom petals on a spring day.

The archivists transcribe the memories and collaborate with a production

team of cinematographers, designers and art directors to re-create

them into a low-budget film. After a public screening of the finished

films, the dead move on to the afterlife with their single memory.

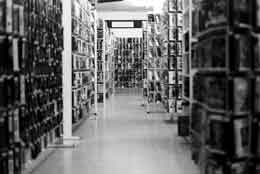

The films are later acquired into the collective "archive" of memory,

and shelved in cans in a climate-controlled storage. Watching Kore-eda's

film, one cannot help but reflect on one's personal life: Is our time

on earth meaningful and memorable? Living in a culture that produces

a surfeit of tele-vision, film and multimedia, imagine the difficulty

of choosing nor only a "real" memory, but also a single memory of

a media event. As entertainment continues to expand into infinite

universes of theaters, streams, channels, webs and networks, our televisual

and filmic memory tends to spill over into our memory of "real" events.

As with Kore-eda's film, the line between fact and fiction blurs.

In "After Life" a young man defiantly chooses not to select a memory.

He argues that because memory is so easily reconstructed, it would

be more "responsible" to choose a dream or a memory of the future.

Acknowledging that the human brain cannot possibly hold all recordings

of mediated memory, museums in the middle of the 20th century took

upon the role of archiving these images by establishing photography

and film departments. More recently, museums have created video archives.

The Jewish Museum in New York established the National Jewish Archive

of Broadcasting in 1981 with the purpose of collecting, preserving,

and exhibiting broadcast material pertaining to the Jewish experience.

The NJAB is a collection of over 4000 audio and video programs from

1948 to the present that pertain to the Jewish experience. The collection

includes a variety of broadcast genres including documentary, advertising,

news, drama and comedy. These time-based artifacts are exhibited with

the rest of the Museum's collection of 30,000 artworks and physical

objects. By generating diverse educational programs, the NJAB not

only serves the Museum, but also the academy, the industry, and the

general public interested in expressions of Jewishness in media. However,

a broadcast collection in the context of an art museum is at times

an awkward fit from the perspective of both the curator and the maker.

Of course, television and radio do not share the same qualities of

conoisseurship that curators apply to fine art. In the early years

of television, most independent producers did not create costly kinescopes

of their broadcasts because they thought the public  would

not be interested in their work in the future. In addition, both visual

artists and television producers believed that their work was created

in a particular moment - any attempt at preservation and re-creation

was unthinkable or absurd. Only recently have film and photography

secured their place in the museum storage rooms and galleries. Video

and other contemporary ephemera (digital art, installation, performance,

etc.) are just beginning to be actively acquired, cataloged and accessioned

- and with great difficulty. Even in climate-controlled storage, video

has a limited shelf life. The rapid obsolescence of equipment and

formats (2", 1", ²", Pi", Betamax, VHS, Betacam SP, Digital Betacam,

D1, D2, D3, DV, DVD, etc.) pose the greatest challenge to video preservation.

In "After Life", reality is recorded and logged on videotape and used

by the dead as reference for selecting a memory. Their re-constructed

memories are recorded on film, a media with established preservation

protocols. "After Life" reflects the notion that raw video footage

appears both more immediate and more ephemeral than a crisply edited

film. Indeed, if video reflects our raw reality, and the public con-tinues

to make greater demands for the re-birth of its televisual heritage,

perhaps a greater amount of attention should be directed towards video

preservation. An archive or museum is often likened to a cemetery

- a place where art and artifacts go to die after they are no longer

circulating in the market. However, many media archivists and curators

are seeking out methods of preservation and finding new uses for media

as cultural artifacts. Most importantly they are striving to reinvent

the museum-archive as an afterlife according to Kore-eda's vision:

a site of dialogue and creativity. c. page 6 On Board the Media Bus:

Harold's Bar Mitzvah and Guerilla Television The Jewish Museum's National

Jewish Archive of Broadcasting collects television and radio pertaining

to the Jewish experience including Seinfeld episodes, Manischewitz

wine commercials, public television documentaries, and alternative

programs that sometimes do not fit neatly into traditional genres.

One of the most important examples of independent broadcasting in

the collection is Harold's Bar Mitzvah (1977), a 30-minute video by

Bart Friedman which was first shown at The Jewish Museum in the 1988

exhibition Time and Memory: Video Art and Identity. Narrating behind

the camera, Friedman guides the viewer in three sections through the

preparation and celebration of a coming-of-age ceremony. Part home

movie and part social commentary, Harold's Bar Mitzvah is above all

a gift to the young man. At the end of the video, Friedman includes

a dedication in titles: "So Harold, you see a good bar mitzvah consists

of eating, dancing and singing - may your life be like a bar mitzvah."

The video begins with Sam and Miriam Ginsberg at home preparing for

their grandson's event. Sam models his fifteen year-old suit as his

proud wife brushes out the wrinkles and confirms that Harold's check

is in her husband's pocket. The Ginsbergs proceed to drive from the

Catskill Mountains to Temple Emanu-El in Lynbrook, Long Island. In

honor of the Sabbath, the rabbi refuses Friedman's request to tape

the actual service, but generously offers to recreate the ceremony

on the following day. In the manner of a Hollywood movie mogul, the

rabbi sternly orders the family to take their places on the pulpit

and directs the mise-en-scene. The final section, containing footage

of the party at Fontainebleau Caterers, provides a striking contrast

with the first section in which we hear Sam's Yiddish melodies. Amid

flash photography, wet kisses, and the "hokey-pokey," Friedman's camera

captures wishes of health and wealth from the multi-generational guests.

The alternative media movement took root in Sam and Miriam Ginsberg's

home in upstate New York, close to the vacation resorts of the "Borscht

Belt." The invention of the Sony Portapak in 1965 enabled artist/activists

like Friedman, who challenged what was perceived as government and

corporate control of public information, to paint portraits of inhabitants

on the margins of the American landscape using electronic imaging

tools. Friedman and his colleagues formed Media Bus (an off-shoot

of the Soho artist collective Videofreex) and established Lanesville

TV in 1972 as the world's first pirate television station. The Ginsbergs

of Lanesville, NY rented their twenty-room farmhouse to Media Bus,

where Friedman and his colleagues produced and illegally broadcasted

some of the first community-based videos. In describing the mission

of Media Bus, Friedman states that, "radical hippie video social documentarian

artists took every opportunity to examine the quirks of people and

their institutions." As Eastern European immigrants with radical,

left-wing politics, the quirky Ginsbergs provided a supportive atmosphere

in which Media Bus was able to flourish. The pioneering work of Friedman

and Media Bus ultimately paved the way for today's community cable

television and the internet where concepts of public access and participation

are often taken for granted. Harold's Bar Mitzvah is one of the most

significant works in the collection of the National Jewish Archive

of Broadcasting because of its content and context. Friedman was one

of the earliest artists to examine Jewish themes in the evolving body

of work then known as "video art." His video captures the intersection

of two generations and two cultures of Old World and New World. It

is a dialogue between a young filmmaker and his elderly subject who,

despite gaps in generation and culture, share a passion for life,

humor, radicalism and Yiddishkeit. Produced during the wake of racial

pride and "power to the people," Harold's Bar Mitzvah demonstrates

the desire of Jewish artists to express their ethnicity -- something

which many of their parents aggressively concealed - and to reject

corporate America. Andrew Ingall, M.A. is Coordinator of the National

Jewish Archive of Broadcasting at The Jewish Museum, New York and

a founding member of Independent Media Arts Preservation. The Jewish

Museum will present Harold's Bar Mitzvah in Moving Portraits: The

Jewish American Family in Video Art and Alternative Media in Winter

1999-2000.

would

not be interested in their work in the future. In addition, both visual

artists and television producers believed that their work was created

in a particular moment - any attempt at preservation and re-creation

was unthinkable or absurd. Only recently have film and photography

secured their place in the museum storage rooms and galleries. Video

and other contemporary ephemera (digital art, installation, performance,

etc.) are just beginning to be actively acquired, cataloged and accessioned

- and with great difficulty. Even in climate-controlled storage, video

has a limited shelf life. The rapid obsolescence of equipment and

formats (2", 1", ²", Pi", Betamax, VHS, Betacam SP, Digital Betacam,

D1, D2, D3, DV, DVD, etc.) pose the greatest challenge to video preservation.

In "After Life", reality is recorded and logged on videotape and used

by the dead as reference for selecting a memory. Their re-constructed

memories are recorded on film, a media with established preservation

protocols. "After Life" reflects the notion that raw video footage

appears both more immediate and more ephemeral than a crisply edited

film. Indeed, if video reflects our raw reality, and the public con-tinues

to make greater demands for the re-birth of its televisual heritage,

perhaps a greater amount of attention should be directed towards video

preservation. An archive or museum is often likened to a cemetery

- a place where art and artifacts go to die after they are no longer

circulating in the market. However, many media archivists and curators

are seeking out methods of preservation and finding new uses for media

as cultural artifacts. Most importantly they are striving to reinvent

the museum-archive as an afterlife according to Kore-eda's vision:

a site of dialogue and creativity. c. page 6 On Board the Media Bus:

Harold's Bar Mitzvah and Guerilla Television The Jewish Museum's National

Jewish Archive of Broadcasting collects television and radio pertaining

to the Jewish experience including Seinfeld episodes, Manischewitz

wine commercials, public television documentaries, and alternative

programs that sometimes do not fit neatly into traditional genres.

One of the most important examples of independent broadcasting in

the collection is Harold's Bar Mitzvah (1977), a 30-minute video by

Bart Friedman which was first shown at The Jewish Museum in the 1988

exhibition Time and Memory: Video Art and Identity. Narrating behind

the camera, Friedman guides the viewer in three sections through the

preparation and celebration of a coming-of-age ceremony. Part home

movie and part social commentary, Harold's Bar Mitzvah is above all

a gift to the young man. At the end of the video, Friedman includes

a dedication in titles: "So Harold, you see a good bar mitzvah consists

of eating, dancing and singing - may your life be like a bar mitzvah."

The video begins with Sam and Miriam Ginsberg at home preparing for

their grandson's event. Sam models his fifteen year-old suit as his

proud wife brushes out the wrinkles and confirms that Harold's check

is in her husband's pocket. The Ginsbergs proceed to drive from the

Catskill Mountains to Temple Emanu-El in Lynbrook, Long Island. In

honor of the Sabbath, the rabbi refuses Friedman's request to tape

the actual service, but generously offers to recreate the ceremony

on the following day. In the manner of a Hollywood movie mogul, the

rabbi sternly orders the family to take their places on the pulpit

and directs the mise-en-scene. The final section, containing footage

of the party at Fontainebleau Caterers, provides a striking contrast

with the first section in which we hear Sam's Yiddish melodies. Amid

flash photography, wet kisses, and the "hokey-pokey," Friedman's camera

captures wishes of health and wealth from the multi-generational guests.

The alternative media movement took root in Sam and Miriam Ginsberg's

home in upstate New York, close to the vacation resorts of the "Borscht

Belt." The invention of the Sony Portapak in 1965 enabled artist/activists

like Friedman, who challenged what was perceived as government and

corporate control of public information, to paint portraits of inhabitants

on the margins of the American landscape using electronic imaging

tools. Friedman and his colleagues formed Media Bus (an off-shoot

of the Soho artist collective Videofreex) and established Lanesville

TV in 1972 as the world's first pirate television station. The Ginsbergs

of Lanesville, NY rented their twenty-room farmhouse to Media Bus,

where Friedman and his colleagues produced and illegally broadcasted

some of the first community-based videos. In describing the mission

of Media Bus, Friedman states that, "radical hippie video social documentarian

artists took every opportunity to examine the quirks of people and

their institutions." As Eastern European immigrants with radical,

left-wing politics, the quirky Ginsbergs provided a supportive atmosphere

in which Media Bus was able to flourish. The pioneering work of Friedman

and Media Bus ultimately paved the way for today's community cable

television and the internet where concepts of public access and participation

are often taken for granted. Harold's Bar Mitzvah is one of the most

significant works in the collection of the National Jewish Archive

of Broadcasting because of its content and context. Friedman was one

of the earliest artists to examine Jewish themes in the evolving body

of work then known as "video art." His video captures the intersection

of two generations and two cultures of Old World and New World. It

is a dialogue between a young filmmaker and his elderly subject who,

despite gaps in generation and culture, share a passion for life,

humor, radicalism and Yiddishkeit. Produced during the wake of racial

pride and "power to the people," Harold's Bar Mitzvah demonstrates

the desire of Jewish artists to express their ethnicity -- something

which many of their parents aggressively concealed - and to reject

corporate America. Andrew Ingall, M.A. is Coordinator of the National

Jewish Archive of Broadcasting at The Jewish Museum, New York and

a founding member of Independent Media Arts Preservation. The Jewish

Museum will present Harold's Bar Mitzvah in Moving Portraits: The

Jewish American Family in Video Art and Alternative Media in Winter

1999-2000.