|

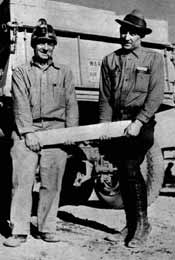

Hundred pound gold bar mined in theAntelope Valley ca. 1936 |

Cool Ranch, the location of "Line of Sight," is in the Antelope Valley, which is at the western end of the Mojave Desert. This is a landscape that is more defined by a web of lines that criss-cross and overlap it than by the activities that take place on it. The lines covering the hard, dry valley floor are scars of nature's power, and man's attempt to use the land to best serve his needs. Through the understanding of the history of these lines, one can gain a nearly complete understanding of the region. The story that is told is that of a region in constant flux. Everything about the area is in motion, be it the transient population, the ever-changing means of production, man's constant manipulation of the natural landscape, the passing of travelers through the area, or the movement of the earth itself. It is this web of lines that allows the valley to function at all. Without them, the area would be one of stagnation, and death. c. page 2 The Antelope Valley and Cool Ranch share similar history, in both the creation of the natural environment, and the exploitation of the land. Both are areas that have been continually explored in the hopes of finding one industry that could prove lucrative; yet none has had long-lasting success. As a result, the valley has a chameleon-like feel. Gold mining, farming, cattle, borax, stagecoaches, railroads, aviation, drugs, and various other endeavors constitute the history this valley with no identity. The Antelope Valley is a landscape that is not fully understood at first glance. Most of what happens here happens "behind the scenes," be it the lines that mark out the flow of water or the "secret" industries that are scattered around the high desert terrain. The most recent industries, the aerospace industry and the drug trade, have required top-secret standing. These two industries happen within a few miles of major developments, yet are totally imperceivable. The byproducts of both industries are consumed or used by a populace outside of the Antelope Valley: the Stealth bomber is stationed at Kirtland Air Force base in New Mexico, and the drugs manufactured in the area are dispersed to metropolitan areas of the West. Production taking place in the Valley is not apparent until it passes outside of its boundaries. But just as much as the products leave, the industries also have a tendency to pack up and go. The Antelope Valley is a tentative, provisional landscape. Before man's

|

Los Angeles Aqueduct near Jawbone Siphon, ca 1910 |

inhabitation of the valley, it was shaped by the awesome San Andreas Fault. This fault runs 650 miles from Northern California, through the southern deserts, and past the Salton Sea, exiting the continent at the Gulf of Mexico. As it passes through the Antelope Valley, it runs along the northern part of the San Gabriel range. While the fault remains unseen from the valley floor, a visitor to the area can sense that this secluded area was created by some natural force. In fact, the two largest earthquakes ever recorded in California history occurred just north of the Antelope Valley, one at Fort Tejon and one in Tehachapi. Both of these measured 7.7 on the Richter Scale. This is the line that made the valley into the dry and arid place that it is, by creating mountains that obstructed moisture from entering the valley, turning the area into a desert landscape. The valley is made up like a basin, into which numerous alluvial fans empty all the waters flowing from higher elevations. The western part of the valley is enclosed by the San Gabriel and Tehachapi ranges. But it is the desert floor that most clearly shows the effects the scar that describes the evolution of the valley, ever changing due to both natural forces. One way the line/fault has helped in the history of the valley, and other parts of California, is through the creation of various natural water reservoirs. The Antelope Valley's Quail Lake and nearby Elizabeth Lake were both brought into existence by major earthquakes that shook the earth violently. It is lakes such as these that allow semi-arid Los Angeles and its environs to exist The active relationship between man and nature is clearly illustrated through the numerous water lines that cover the Antelope Valley basin. The California and Los Angeles aqueducts are the two most significant scars that stretch through the valley and out into more populated areas. The water traveling in these aqueducts was never meant for the Antelope Valley, but for people on the other side of the mountains (the "flatlanders"). The aqueducts were seen as "human engineering wonders," and made Southern California what it is today. There is still a debate as to whether William Mulholland's far-fetched water works was good or bad for Los Angeles. While

|

Fairmont Reservoir, where water finaly enters L:A. County |

initially, bringing water allowed Los Angeles to grow as its developer proponents had hoped it would, the long-term results have been over crowding and the problems associated with it, problems that would have been avoided without the extensive water works. The aforementioned lakes are part of the larger array of reservoirs that help keep the right amount of water available to the millions of residents of Southern California. This is a natural lake caused by an earthquake, made to work on behalf of human needs. Quail Lake, and all of the other reservoirs in the region were developed as provisional measures to ensure that in the event that existing aqueduct systems were to fail, The Los Angeles Metropolitan Areas would be supplied with water for at least six months. Failure of the aqueduct system could be caused by a number of events, the most significant of which would be a major earthquake, caused by one of the many faults that characterize this region and all of California. The one stream of continuity that exists in both the Antelope Valley and at Cool Ranch is that they are both places to "make it through" more than places to reside, from the days of the Pony Express to the present-day weekend traveler. Consider the origins of Lancaster - the Southern Pacific Rail Road. Lancaster was just an intermediate stop on a trip from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Cool Ranch, also, has historically been a stop "along the way." The major scars of Cool Ranch are the trails that make travel within the property possible, as well as the lines created by the wheels of the stagecoach that once traveled through here. Baldwin Canyon, the canyon that runs North-South through the property, had one of the oldest structures in the Antelope Valley, a stagecoach stop along the Butterfield route. This was the route between the Antelope Valley and Los Angeles, as well as the major route used to transport goods between Los Angeles and Fort Tejon. While the stagecoach has not passed through here in over one hundred years, the lines of the stagecoach wheels will remain far beyond our lives. Several other sets of lines exist in the Antelope Valley as a result of operations at Edwards Air Force Base, which prides itself as the most prestigious air-testing center in the United States. Adding to the complex web of lines running through the larger area are the lines of the runway; the lines inscribed in the earth by the landing of high-speed, experimental aircraft, such as the Space Shuttle and many others; and the overhead flight paths going to and from the Base. The Air Force Base is currently the major economic powerhouse of the Antelope Valley. The first man to break the sound barrier was based at Edwards, as is Skunk Works (otherwise known as Plant 42), the highly classified airplane manufacturing plant. It is amazing to think that the ever-expanding suburban development of Lancaster/Palmdale is encroaching on such a nationally sensitive area. The base has a larger buffer of dirt and sagebrush, a difficult terrain to cross without getting caught by unseen authorities. Also in the area are three "Radar Cross Section Facilities" for testing stealth technology. The closest of the three is Northrop's Tejon facility - oddly enough across the valley, just north of Cool Ranch. Cool Ranch has a recent history even more taboo than most of the Antelope Valley, involving the manufacturing of drugs, and the inadvertent destruction of its previous history. Even in this wide-open space, the newer industries have a tendency of obliterating the remains of the old. The previous owners ran a meth-lab in the 130-year-old stagecoach structure, secluded in Baldwin Canyon. Because of the remoteness of Cool Ranch, and its location being a strategic vantage-point for viewing encroaching authorities in the valley below, this made for a perfect setting. The only way of detecting a meth-lab is through heat-sensing devices. The Antelope Valley makes a prime candidate for the production of meth, because meth labs generate so much heat that it radiates out of the buildings. By the mere fact that the desert floor is already hot (most likely as hot as the building), chances of the sensors ever picking it up are slim in the sun-baked landscape. The only reason it was ever discovered was because the inept drug dealers ran electricity through speaker wire. As the wire got hot, it burned through its insulation, and sparked a brush fire. This brush fire went east towards Lancaster/Palmdale, over three hills. By the time the fire and police departments arrived, the owners of the property had already vacated, upon noticing the brush fire that they had started. All of their belongings were scattered throughout the property and the buildings. Both the Antelope Valley and the microcosm that is Cool Ranch owe much of their existence and history to the activities that the lines inscribe. These lines are as grand as the Valley itself. Amazing that passage through a valley can be so instrumental to the success of surrounding areas, but that at the same time such activities are not acknowledged. Through this show, I hope to illustrate the idea of the line and how it is instrumental in the description and perception of a space (or a space within a space for that matter). The open space of a desert like this is the only place that a line of enormous proportions can exist without being noticed.